The residential construction industry is being flooded with a raft of new products that are aimed at those who are finally beginning to understand some of the basic physics at work in their buildings; the framers and contractors are becoming what is now referred to as “Building Science” savvy.

These products consist mainly of new structural sheathing materials to be installed with specific tapes or sealants, and various membranes intended to be installed on the exterior of the wall or roof that have various properties with respect to their air infiltration resistance, vapor permeability, self-healing properties, and ability to resist deterioration due to exposure to ultra-violet light and ozone. There are also intensive marketing efforts of the various insulation manufacturers aimed at the community of design/construction specifiers responsible for creating the various sandwich assemblies of materials for exterior wall and roof construction. It’s a tangle of information out there that can be at its best overwhelming and at its worst contradictory and confusing making the selection of products and design of wall and roof assemblies difficult, painful and worrisome in terms of building longevity and designer’s and contractor’s liability and responsibility in our ever increasingly litigious society.

Makes one want to throw in the towel some days and change careers to juggler or musician – something where clients don’t complain or come back at you with a law suit.

Here’s a brief history of how we got into this mess. Used to be that we were all taught to put a vapor barrier on the warm side of the wall and be done with it. Buildings were compared to people and “had to breathe.” There was only 15 pound “tar paper” as a building wrap under the siding and the only issue to be wary of was wind-driven water infiltration. The best buildings had 30 pound felt carefully applied to the outside of the wall in a shingled manner to guard against bulk water infiltration, and the contractor or architect just might hold the insulation contractor’s feet to the fire insisting that the tabs on the paper (or foil) faced batt insulation be fastened to the inside stud edge and not the face with the staple hammer, as per the manufacturer’s instructions. I constantly battled the insulation installer who claimed that the “fish-mouths” and other lumps and bumps had the drywall installers complaining that they couldn’t get their drywall installed tightly, there would be resistance and then finally what looked like nail-pops but was the drywall finally settling in tighter to the wall. Anyway, it caused finishing call-backs. O.K. ! O.K. ! Point taken. This resulted in the spec being changed to unfaced batt insulation with a separate vapor barrier – usually 6 mil polyethylene. This was a step up, a tiny bit more costly, but the film could now be installed over the plates and around corners with one stud-bay overlaps.

In those days I was trying every kind of wall I could think of to improve conductive resistance; cross-furring, double walls, Larson trusses (double studs held apart by intermittent squares of plywood making 8” or even 16” thick walls) and trying different placements within the wall to prevent wiring from puncturing the vapor barrier. But all these punctured the budget.

Makes one want to throw in the towel some days and change careers to juggler or musician – something where clients don’t complain or come back at you with a law suit.

Here’s a brief history of how we got into this mess. Used to be that we were all taught to put a vapor barrier on the warm side of the wall and be done with it. Buildings were compared to people and “had to breathe.” There was only 15 pound “tar paper” as a building wrap under the siding and the only issue to be wary of was wind-driven water infiltration. The best buildings had 30 pound felt carefully applied to the outside of the wall in a shingled manner to guard against bulk water infiltration, and the contractor or architect just might hold the insulation contractor’s feet to the fire insisting that the tabs on the paper (or foil) faced batt insulation be fastened to the inside stud edge and not the face with the staple hammer, as per the manufacturer’s instructions. I constantly battled the insulation installer who claimed that the “fish-mouths” and other lumps and bumps had the drywall installers complaining that they couldn’t get their drywall installed tightly, there would be resistance and then finally what looked like nail-pops but was the drywall finally settling in tighter to the wall. Anyway, it caused finishing call-backs. O.K. ! O.K. ! Point taken. This resulted in the spec being changed to unfaced batt insulation with a separate vapor barrier – usually 6 mil polyethylene. This was a step up, a tiny bit more costly, but the film could now be installed over the plates and around corners with one stud-bay overlaps.

In those days I was trying every kind of wall I could think of to improve conductive resistance; cross-furring, double walls, Larson trusses (double studs held apart by intermittent squares of plywood making 8” or even 16” thick walls) and trying different placements within the wall to prevent wiring from puncturing the vapor barrier. But all these punctured the budget.

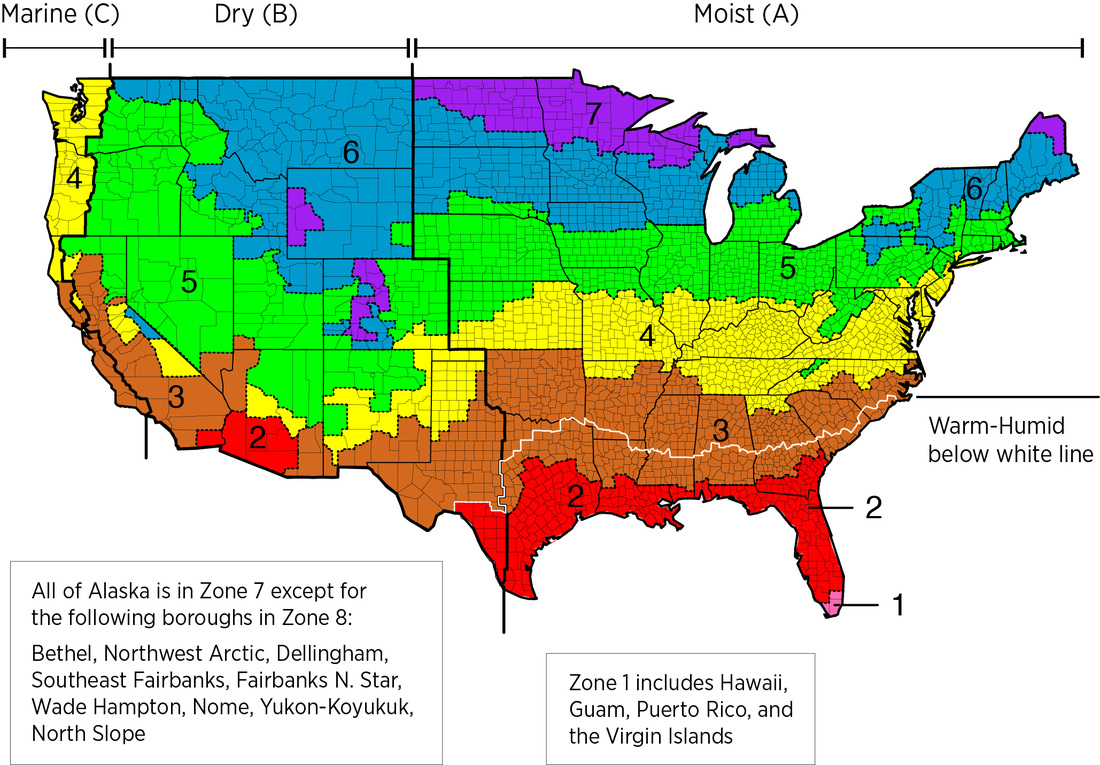

The troubles began when we all started to learn about the importance of having the building “tight” or sealed up against air infiltration. We learned that there was real danger in having warm moist air condense within the wall. Not only could there be mold and mildew which could spread through the perfect medium – gypsum wallboard – but the structural integrity of the wall could be at risk due to rot. We had started the era of “Sick Building Syndrome” and there was actually significant blow-back against energy loss mitigation strategies due to fear of creating a sick building. While, as expected, many of these buildings with condensation within the walls occurred in the climate zones with the higher numbers, those where the mechanical equipment was utilized mostly for heating, there were also a shocking number of buildings with the same symptoms in climate zones one, two, and three, where mechanical cooling hours prevailed.

Certainly there were many cases where “somebody goofed” and the vapor barrier was on the wrong side of the wall, not the warm side of the wall, but there were many cases where the construction was as it should have been but what caused the problem was a classic example of “User patterns trump engineering.”

Out on the east end of Long Island, NY where I live and practice a whopping 65% of the entire housing stock are second homes – embarrassingly large vacation houses for the very wealthy class, the “one percent.” These homes, located in climate zone 4 with a 5750 heating degree day climate, are vacant during the cold months with thermostats turned way down or even off with the plumbing drained and populated during the summer with a crowd operating in “vacation mode” not conservation mode like the rest of us. They have even reduced matters further by eliminating the swing seasons. The air conditioning is always on, even with doors and windows open. The run time for the AC equipment far outpaces the run time for the heating equipment. So with a vapor barrier positioned within the wall for a heating climate, it is now in the wrong place effectively acting to pump vapor into the wall where hits the cold interior and condenses. Oooops !

Well, the industry offers me many options so I don’t have to have that problem anymore. In fact, there are more types of insulation alone, plus different sheathing materials and sealing tapes and caulks and liquid-applied barriers so I can choose from several different materials and methodologies in order to get a high-performing wall with just a very small chance of condensation within. (Don’t forget that ‘user-patterns-trump-engineering” caution.) Wading through all this material and trying to keep track of it, figure the labor costs for correct installation and field check that it has actually been installed as specified becomes a real job. All this stuff exists just to remediate the inherent qualities of stick (wood or metal) framing.

The problem is the cavities.

SIP construction is Cavity – Free.

SIPs provide that all-important continuous insulation wrap without any thermal bridges, any cavities, any need for additional caulking and sealing, or the need for any vapor barriers. Period. The true “one-stop shop” with built-in qualities inherently resistant to condensation. As the amount of remediation materials and technologies increase, and the regulatory environment continues to become more and more stringent, and the cost of labor continues to rise, SIPs look better and better.

So aside from all the features of SIPs that SIPA and other SIP manufacturers brag about, don’t forget the unsung hero of the SIP world – no more cavities, mom !

Out on the east end of Long Island, NY where I live and practice a whopping 65% of the entire housing stock are second homes – embarrassingly large vacation houses for the very wealthy class, the “one percent.” These homes, located in climate zone 4 with a 5750 heating degree day climate, are vacant during the cold months with thermostats turned way down or even off with the plumbing drained and populated during the summer with a crowd operating in “vacation mode” not conservation mode like the rest of us. They have even reduced matters further by eliminating the swing seasons. The air conditioning is always on, even with doors and windows open. The run time for the AC equipment far outpaces the run time for the heating equipment. So with a vapor barrier positioned within the wall for a heating climate, it is now in the wrong place effectively acting to pump vapor into the wall where hits the cold interior and condenses. Oooops !

Well, the industry offers me many options so I don’t have to have that problem anymore. In fact, there are more types of insulation alone, plus different sheathing materials and sealing tapes and caulks and liquid-applied barriers so I can choose from several different materials and methodologies in order to get a high-performing wall with just a very small chance of condensation within. (Don’t forget that ‘user-patterns-trump-engineering” caution.) Wading through all this material and trying to keep track of it, figure the labor costs for correct installation and field check that it has actually been installed as specified becomes a real job. All this stuff exists just to remediate the inherent qualities of stick (wood or metal) framing.

The problem is the cavities.

SIP construction is Cavity – Free.

SIPs provide that all-important continuous insulation wrap without any thermal bridges, any cavities, any need for additional caulking and sealing, or the need for any vapor barriers. Period. The true “one-stop shop” with built-in qualities inherently resistant to condensation. As the amount of remediation materials and technologies increase, and the regulatory environment continues to become more and more stringent, and the cost of labor continues to rise, SIPs look better and better.

So aside from all the features of SIPs that SIPA and other SIP manufacturers brag about, don’t forget the unsung hero of the SIP world – no more cavities, mom !

RSS Feed

RSS Feed